Crikey’s series explores Opposition Leader Peter Dutton’s history of racism as well as the role racism has played on both sides of politics since the 1970s. Race and racism have long played a role in Australian politics. But Peter Dutton stands out as the most plainly racist Australian political leader since the White Australia policy. Here's the proof.

Crikey’s series explores Dutton’s history of racism as well as the role racism has played on both sides of politics since the 1970s.

Race and racism have long played a role in Australian politics. Malcolm Fraser was attacked by Labor for extending humanitarian migration to South Vietnamese refugees. John Howard sought to weaponise Asian migration in the 1980s. In the wake of 9/11 and Tampa, the Howard government made a virtue of its tough line on asylum seekers and Australians of Muslim background, while Howard’s refusal to engage with Indigenous peoples came to characterise his prime ministership. The rise of the Islamic State once again saw Australia’s Muslim community targeted by Coalition politicians. The Gillard government made a virtue of its crackdown on temporary migrants.

But Peter Dutton stands out as the most plainly racist Australian political leader since the White Australia policy. Read the proof on the Crikey website.

Comments are switched off on this article.

Back to topBoth sides of politics have exploited racism over the past 50 years. But Peter Dutton is unusual among the recent generation of politicians in displaying overt racism.

This article is an instalment in a new series, “Peter Dutton is racist”, on Dutton’s history of racism and the role racism has played on both sides of politics since the 1970s.

Racism has been a recurring theme in Australian politics ever since the Whitlam government formally ended the White Australia Policy.

Labor — under Whitlam — resisted accepting South Vietnamese refugees (Whitlam is described as referring to them as “fucking Vietnamese Balts“), with Whitlam anticipating Peter Dutton by nearly 50 years in suggesting their ranks might include war criminals.

In opposition, Labor criticised the Fraser government’s willingness to welcome South Vietnamese refugees to Australia after 1975. “Any sovereign nation has the right to determine how it will exercise its compassion and how it will increase its population,” then ACTU leader Bob Hawke said in 1977 — as Gerard Henderson noted, thus sounding a lot like John Howard later would.

John Howard’s first period as Liberal leader saw him attempt to weaponise racism by calling for a reduction in Asian immigration in the name of “social cohesion” in 1988. Howard later apologised for the remarks. In office, and especially after 9/11, Howard’s government demonised Middle Eastern refugees — most notably via fake claims in the “children overboard” scandal — usually in exactly the terms that Labor had employed against South Vietnamese boat people.

Pauline Hanson began her career in the election that brought Howard to power in 1996, and made racism — initially directed against Australians of Asian heritage, and then Muslim Australians — the basis for what has turned out to be a lengthy political career, even if much of it was spent out of Parliament. A number of politicians — always older white men — have had their own forays into politics on her political coattails.

Howard’s government was also marked by hostility toward Indigenous peoples, particularly via the Northern Territory Intervention, which Labor backed, and his refusal to apologise to the Stolen Generations. Kevin Rudd’s Apology in 2008 marked the beginning of around 15 years of relative bipartisanship on both the Apology and the challenge of Closing The Gap — a period ended by Peter Dutton and his decision to oppose constitutional recognition of Indigenous peoples and a Voice to Parliament.

The past 30 years have been more characterised by “dog-whistling” than open racism of the kind displayed by Labor and by Howard in the 1970s and 1980s. Indeed, claims of racism are now angrily denied by major party politicians. But both sides of politics have sought to use racism-adjacent issues, such as refugees or temporary migration, for political purposes.

The Coalition has long owned border security as a political issue — despite the loss of control of Australia’s borders to people smugglers and illegal immigrants under Dutton as Home Affairs minister. Migration, however, has been more contested: the Gillard government sought to exploit the issue of concerns about temporary migration by announcing it was cutting back on what were then “457 visas”. Labor and the Coalition are presently engaged in a kind of reverse auction on temporary migration, with each seeking to outbid the other on who can cut foreign student and temporary worker numbers more, while the Coalition under Dutton has sought to link Labor’s poor handling of the High Court’s changes to immigration detention to the threat of criminal refugees attacking Australians.

Is Dutton, who now calls for a ban on Palestinians entering Australia because they’re a potential security threat, thus any different to leaders on both sides of politics who have sought to use racism-adjacent issues for political gain? There are more than a dozen instances of Dutton making remarks that engage in race-baiting, or the exploitation of race-adjacent issues, since 2008. But there are three specific and overt sets of remarks that suggest that for Dutton, racism isn’t merely a political tool, but a personal belief that he thinks is relevant to public policy.

In 2010, Dutton defended colleague Wilson Tuckey, who had attacked acknowledgements of Traditional Owners as a “farce”, suggested Indigenous peoples had only got a “population of 300,000 people” out of Australia, and claimed that the 1967 referendum was “the worst thing that’s happened for Aboriginal people in history”. Dutton not merely supported Tuckey’s right to say his comments, but went further, saying “I don’t have any issue with what Wilson said frankly or his right to say it.” Dutton also famously boycotted Rudd’s Apology two years before, an action he now says was a mistake.

The second is Dutton’s hostility toward non-white refugees. He criticised the Fraser government for allowing Lebanese refugees into Australia, described refugees as illiterate, innumerate and simultaneously taking jobs from Australians and “languish[ing] in unemployment queues and on Medicare and the rest of it”, argued (conversely) that people found to be refugees in fact were wealthy economic migrants, claimed that African gangs (the alleged product of Sudanese refugees) were terrifying Melburnians — and, most recently, argued all Palestinian refugees fleeing the onslaught in Gaza are potential national security threats.

But there’s one group of refugees Dutton is very welcoming of: white people. In 2018, Dutton ordered the Home Affairs Department to examine ways to help white South African farmers flee to a “civilized” country like Australia. White South Africans “work hard, they integrate well into Australian society, they contribute to make us a better country and they’re the sorts of migrants that we want to bring into our country.”

To be hostile to refugees or migration per se may not necessarily be racist, though the former is frequently due to the latter. But Dutton has explicit racial preferences in refugees — white refugees are good; brown and Black refugees are illiterate, innumerate, lazy, economic migrants, security threats and prone to forming criminal gangs.

The third is Dutton’s false claim in November 2018 that Australia’s Muslim communities had hampered counter-terrorism efforts. In the wake of the fatal Bourke St attack by Hassan Khalif Shire Ali, Dutton said “it is a time for community members to step up … We need to be realistic about the threat and the idea that community leaders would have information, but withhold it from the police or intelligence agencies is unacceptable.”

In fact there was no evidence that anyone had withheld information about Shire Ali. Shire Ali was well-known to police and ASIO — which by then was in Dutton’s own portfolio — at the time of the attack and he had had his passport cancelled. An AFP assessment determined he did not pose a threat to national security. If anyone had failed, it was Dutton’s own agency. Yet he singled out Muslim Australians as somehow responsible for Shire Ali’s attack.

Indigenous peoples. Brown and black-skinned refugees. Muslims. Dutton has attacked each group, or endorsed attacks on them. He continues to do so. Other political leaders might dog-whistle, or pursue racism-adjacent issues. Dutton does that, as well — but he goes further. He’s overtly racist — something Australia hasn’t seen in a national leader since John Howard’s repudiated remarks in the 1980s.

Do you think Peter Dutton is racist? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Comments are switched off on this article.

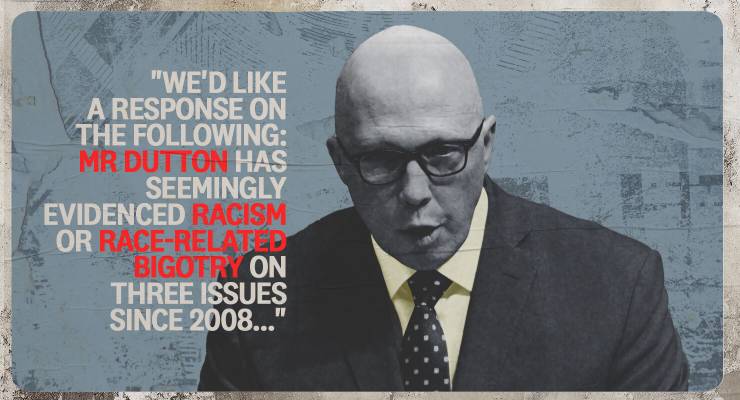

Back to topCrikey asked Peter Dutton to respond on three specific charges of racism over the last 15 years. We're yet to hear back.

This article is an instalment in a new series, “Peter Dutton is racist”, on Dutton’s history of racism and the role racism has played on both sides of politics since the 1970s.

On August 29, Crikey emailed Peter Dutton’s office with the following request, then followed it with a text message and phone call last week and another phone call today. We’re yet to receive a response to the message below.

Crikey is preparing a series of articles on racism in Australian politics and the exploitation of racism by Labor and the Coalition parties, including an article on Mr Dutton’s comments over the years on race or race-related issues.

We’d like a response on the following:

Mr Dutton has seemingly evidenced racism or race-related prejudice on three issues since 2008:

- In March 2010 he was reported as endorsing comments by Wilson Tuckey, that acknowledgements of traditional owners were a “farce”, that some Indigenous people who perform Welcome To Country ceremonies were “grossly overweight”, that the “best” Indigenous people had got out of Australia was a “population of 300,000 people” and the 1967 referendum “was the worst thing that’s happened for Aboriginal people in history”. Mr Dutton was reported as responding to the comments “I don’t have any issue with what Wilson said frankly or his right to say it.”

- Mr Dutton has long been critical of refugees and asylum seekers — that they’re illiterate and take jobs or languish in jobless queues, that the Fraser government should not have allowed Lebanese-Muslim refugees in, references to “Armani refugees”, or his recent opposition to Palestinian refugees being admitted from Gaza. However, Mr Dutton has supported the entry of white South African farmers fleeing violence in South Africa, suggesting racial preference.

- In November 2018 in the wake of a fatal attack by Hassan Khalif Shire Ali in Bourke St in Melbourne, Mr Dutton said “But it is a time for community members to step up … We need to be realistic about the threat and the idea that community leaders would have information, but withhold it from the police or intelligence agencies is unacceptable.” There was no public evidence that Muslim community leaders withheld any evidence about Shire Ali, who had been vetted by ASIO, an agency that was in Dutton’s own portfolio at the time.

Questions:

- Does Mr Dutton stand by his comments in each of these instances? (He has reported to have apologised in relation to comments about Lebanese Muslims, but we can’t find a source.)

- Do these examples indicate that Mr Dutton either holds, or endorses others holding, critical views of Indigenous people, a racial preference regarding refugees coming to Australia and unjustified criticism of the Muslim community of a kind he has not repeated about other groups in the wake of terrorist violence?

- Crikey has also collated the attached collection of quotes from Mr Dutton. Does he believe this is a fair representation of his stance on race or race-related issues?

Do you think Peter Dutton is racist? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Comments are switched off on this article.

Back to topBeing racist is, appropriately, not illegal. Racial discrimination is unlawful. The hard question is determining when the performance of racist beliefs, by words, should be outside the law.

This article is an instalment in a new series, “Peter Dutton is racist”, on Dutton’s history of racism and the role racism has played on both sides of politics since the 1970s.

Racism has two meanings, and it’s important to understand which one we’re using.

One is about belief: in the notion that a person’s attributes — including personality, behaviour and characteristics such as intelligence — can be predicted from their racial or ethnic origin.

The other is about action: acts of prejudice, discrimination or antagonism, because of — rooted in — racist belief.

Race is an artificial construct, so racism as a belief system is nonsense. Star signs are more accurate predictors of individual characteristics than signifiers of race, in the sense they are at least based on one objective fact (birth date). Racial classification doesn’t even have that.

How so? Well, while racists flatter themselves with infallible powers of identification, the truth is they’re making guesses based on baseless assumptions. Assumption is not often included in definitions of racism, but it’s an essential element.

Pauline Hanson can best explain how this works. Setting up for a TV interview in 2015, Hanson had this exchange with a cameraman:

Hanson: “You’re not going to tell me you’re a refugee, James, are you?”

James: “No, Aboriginal.”

Hanson: “Really? Wouldn’t have picked it. It’s good to see that you’re actually, you know, taking this up and working.”

Hanson had assumed the cameraman was refugee-probable and not Indigenous, both assumptions based on whatever her little brain thinks people of specific “races” are supposed to look like.

When Peter Dutton applies generic labels to African, Lebanese or Gazan people (or to white South Africans), he is operating on assumptions no less stupid than Hanson’s.

Dutton no doubt does not consider himself racist, as an honest belief. He can make public statements such as his most recent application of the Skittles theory of terrorist identification to the entire population of Gaza, thinking to himself, “I’m not being racist, I’m just pointing out the obvious”.

But what he did there was racist. The Skittles theory, popularised by the philosopher Donald Trump Jnr, is this: if you knew one Skittle in a full bowl was bad, you’d throw them all out. It’s in sync with this argument: not all Muslims are terrorists, but all terrorists are Muslims, so why let any in?

Like all racist theories, it’s factually wrong, pathetically simplistic and dehumanising. It explains the existence and relative popularity of a terrorist organisation like Hamas, not by reference to the conditions imposed externally on Palestinian (or Arabic, or Muslim) people, but as a consequence of something inherent in their character — dictated by their race.

Likewise, Dutton walked out on the Stolen Generations Apology because he was not sorry. He understands the plight of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples — their intergenerational disadvantages — not as being in any way related to what was done to them and their ancestors.

Dutton projects these basic, brutal thoughts by his words — how he talks about every issue of social dysfunction. It’s not hard to discern something he does actually feel: fear. The world must look incredibly dark to him. Again, however, that’s his problem. Our problem is how he externalises his fear in his role as a public leader.

Being racist is, appropriately, not illegal. Racial discrimination as an act that prevents or deters the exercise of ordinary freedoms by others is obviously unlawful. The hard question is determining when the performance of racist beliefs, by words, should be outside the law.

Our current legal test for hate speech is measured by both its effect and its motivation: it must be likely to cause serious harm to its intended victims, but it also must be unreasonable and in bad faith. The legislative guardrails, designed to keep the public square open for vibrant debate on matters of public interest, create only a narrow realm where racist hate speech is rendered illegal. That’s as it should be.

Has Peter Dutton breached Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act? That’s not for me to say, but some of his racially charged statements over the years have sailed very close. They have the potential to hurt whole groups — for example, Lebanese Australians or African Australians — badly. They are offensive, insulting and intimidating. That is particularly so because of the positions he has occupied when saying them.

There is nothing reasonable about attributing antisocial characteristics to people on an arbitrary, evidence-free basis. Nor can it be done in good faith. It’s not in the public interest, and the protestations that people like Dutton make when challenged — I’m just stating the obvious — are disingenuous rubbish. Plausibly deniable racism is still racism.

Whatever fluid flows through Dutton’s heart, that’s not our concern. He is accountable for his chosen speech. Some of that speech is racist.

Do you think Peter Dutton is racist? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Comments are switched off on this article.

Back to topDutton's proposal also marks the first time that that a major party leader has refused point blank to assist people with family links to Australia fleeing a war.

This article is an instalment in a new series, “Peter Dutton is racist”, on Dutton’s history of racism and the role racism has played on both sides of politics since the 1970s.

I was surprised when Peter Dutton called for a ban on Palestinians coming from Gaza. Not because it wasn’t consistent with his appalling record on issues of race. On that front, Dutton is utterly predictable. No, I was surprised because as a former minister responsible for the Migration Act, he would know that banning people of a particular nationality, race or religion is beyond the powers in the act.

It was akin to Donald Trump’s Muslim ban. Trump would have been told once he became US president that such a ban is illegal also in the USA. That was why Trump had to find another way to implement a much more limited visa scrutiny requirement for people of certain nationalities.

While Dutton could demand the Migration Act be amended to provide the power to ban people of a particular nationality, race or religion, that legislative amendment would need to override the Racial Discrimination Act. Dutton or his colleagues have not yet made such a demand — although they, parts of the Murdoch press, and Coalition luminaries such as John Howard continue to support Dutton’s ban in some form or other.

I was less surprised Dutton would make such a call so soon after the race riots in the UK and the ASIO director-general’s warning to political and community leaders to watch their words. Dutton would have little respect for such warnings when there is much political advantage available. He is likely to have made little connection to the Cronulla rioters or the Christchurch mass murderer, both of whom were inspired by parts of the right-wing media and politicians.

Since Dutton’s call for a ban, his colleagues have suggested various explanations for how it might be implemented. Nationals Leader David Littleproud and opposition Home Affairs spokesperson James Paterson have suggested use of Temporary Protection Visas (TPVs) in a ham-fisted attempt to exploit Labor’s decision to abolish these. They seem to have now backed out of using TPVs, perhaps having realised TPVs were for people arriving in Australia unlawfully, mainly boat arrivals, not people arriving with visas.

Labor may decide to implement some form of temporary humanitarian visa in an effort to mitigate its mistake of initially using visitor visas for displaced Palestinians. Visitor visas have the wrong criteria for prioritising people in humanitarian need. For example, a well-off person who has many options for securing visas would likely be prioritised under visitor visa criteria while a child recently orphaned due to the war but with relatives in Australia would not qualify. That is why Australia has usually used humanitarian visas to deal with situations of people fleeing war just as we did when the Taliban took over Afghanistan.

Faced with the current situation in Gaza, the Canadians have allocated 5,000 humanitarian places. That is what we should have done. But that would not prevent Palestinians who have arrived on visitor visas relinquishing their right to apply for a permanent protection visa. Labor should have used permanent humanitarian visas from the outset, just as Canada has done.

That mistake opened the door for Dutton to scare Australians by implying inadequate security checking. That is nonsense.

Palestinians trying to escape Gaza are being closely scrutinised by the Israeli military for any links to Hamas. The Israeli military, more than any organisation on the planet, knows which Palestinians have a link to Hamas. Those Palestinians would never be allowed out of Gaza.

Egypt is also closely scrutinising people escaping Gaza and entering Egypt which houses around 100,000 Palestinian refugees. That country would also have extensive data on Palestinians with links to Hamas.

Australian government scrutiny of visitor visa applicants out of Gaza would use a combination of Movement Alert List (MAL) checks that may include a range of Hamas leaders and operatives, as well as targeted scrutiny of other applicants with characteristics of concern. There would be no point to ASIO scrutinising applicants who have visited Australia many times before, are not on MAL, and have no characteristics of concern.

Palestinians who get a visa to Australia would also be checked at numerous points of travel to Australia and then again checked extensively if they apply for asylum after arrival.

There is no previous cohort that I can recall that would have gone through such extensive security checks.

While Dutton has every right to criticise the Labor government for not using humanitarian visas from the outset, trying to scare Australians about inadequate security checking is just another appalling example of Dutton dog-whistling.

It also marks the first time that that a major party leader in Australia has refused point blank to assist people with family links to Australia fleeing a war. It seems we are no longer the nation that helped displaced Jewish refugees after World War II; refugees fleeing the aftermath of the Vietnam War; Kosovo refugees fleeing the Balkans War; Timorese fleeing the Indonesian Army; people fleeing ISIS rampaging through Syria/Iraq; Afghans fleeing the Taliban; or Ukrainians fleeing the Russian invasion.

Do we really want to traduce our long and proud humanitarian record through a ban on helping Palestinians fleeing the war in Gaza?

Do you think Peter Dutton is racist? Let us know your thoughts by writing to letters@crikey.com.au. Please include your full name to be considered for publication. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.

Comments are switched off on this article.

Back to topThe ABC has created a three-part Australian Story on Lachlan Murdoch. The first hurdle? He wouldn't talk.

Earlier this year, Australian billionaire James Packer had dinner with Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump. At some point the subject turned to Lachlan Murdoch, the heir to the Murdoch media empire. Trump apparently brightened and said something to the effect of, “Oh yeah, I’d like to get to know Lachlan better.”

This is one of investigative journalist Paddy Manning’s favourite revelations from Making Lachlan Murdoch, the three-part Australian Story exploration of one of Australia’s most powerful people. The exchange also goes some way to explaining why the ABC is dedicating a rare three-episode arc to him: for all his power, and all the publicity that has followed him for most of his life, Lachlan Murdoch remains something of an enigma.

“[Packer’s anecdote] tells you something about the difference between Lachlan and [his father] Rupert,” Manning told Crikey. “Trump has known Rupert for 40 years or more. But Trump didn’t meet Lachlan until 2019, when there was a state dinner for Scott Morrison at the White House. So even Donald Trump wants to understand Lachlan better. To me that said a lot.”

Lachlan Murdoch is set to inherit arguably the most powerful media empire in the world. The level of control he exerts over that empire is to be fought out in the courts starting this month, as Rupert — via the ironically named “Project Harmony” — seeks to stop Lachlan’s siblings from shifting their vast media empire away from the political right.

Australian Story executive producer Caitlin Shea told Crikey she had wanted the program to tackle Murdoch for years, but an initial attempt with Manning — around the time the publication of his Murdoch biography The Successor — had failed to “get any traction” with potential interview subjects. Returning to the program at the end of 2023 (having spent a year on the ABC’s Nemesis series), Shea decided it was time to try again.

“He is an important and consequential Australian — he considers himself Australian, he lives here. He wields a lot of power. He’s quite enigmatic,” she said. “And I felt the debate around Lachlan was very polarised … We [at Australian Story] don’t see stories as black and white, we see the shades of grey, and I feel that we’ve been able to bring a lot of nuance to this project.”

A missing subject

The first hurdle was putting together a three-part biography, however nuanced, about a subject who did not wish to participate.

“It became pretty clear early on that Lachlan was not going to participate himself, despite my best endeavours,” Manning said. Manning understands that Murdoch had considered his book The Successor to be a fair portrayal, which “gave me some kind of standing, but nevertheless, he was not prepared to do an interview and he was not prepared to have any serving directors or employees of Fox or News Corp to talk to us either”.

“But I know that in the background there were people who certainly checked in with Lachlan as to whether it would be okay to talk to us and he’s said, ‘Yeah that’s fine.'”

This was doubly important for a “narration-less” program like Australian Story, Shea said.

“All we can put to air is what people tell us,” she said. “That’s why it’s so important to get as many people and a wide range of people to talk to us.”

‘They don’t want to burn a relationship’

Getting a wide roster of on-camera talent isn’t always easy when dealing with a subject as influential and, as Crikey well knows, litigious as Murdoch.

“It’s difficult because there’s a level of fear around Lachlan, in particular because the Murdoch media wields so much power in this country, it’s the most concentrated media market in the world,” Manning said.

“Sometimes the process [of convincing a source to talk on camera] is slow, because people do want to check in with Lachlan himself, because they don’t want to burn a relationship.”

In addition, Manning was shorn of a print journalist’s ability to anonymise sources and weave in information given on background, which made “everything harder” — particularly as, amid the mayhem of “Project Harmony”, the Murdoch clan is “more bitterly divided than it ever has been”.

“It’s very hard to get anyone from the family to talk on the record,” he said. “By definition, it’s a family that’s media savvy, to say the least. And secondly, a family that is at a point of real, genuine difference over the future of the Murdoch empire. We would love to do interviews with Lachlan, with James, with Rupert, and we asked for all of those things, but right now that’s simply not realistic.”

Nevertheless, Manning feels the program has assembled a raft of people — both critics and friends — that can speak on Lachlan “with authority”.

To the archives

Filling the gaps left by their absent subjects meant an arduous search through decades of archives for interviews. Shea said the show’s “incredible producers” had “scoured the world’s archives looking for the best material that we could possibly license”.

“It’s a massive job. It’s expensive. It’s time-consuming,” she said. “But with Lachlan and the family not speaking to us, that was all we could do really to tell their story.”

Manning notes, suggestively, how the archive thins over time with regards to Lachlan — as he racks up high-profile failures to go with his successes, as his responsibilities deepen, Lachlan recedes from public view.

Manning points out that this is another point of difference from Lachlan’s “often disarmingly frank” father.

“A lot of people think you can just substitute the name Lachlan for Rupert, and I think my job is to tease out some of the things that make them different,” he said. “Rupert is in many ways a well-known character, a historical figure. People should know how Lachlan is different. And what are the implications? What does that mean for the future of the Murdoch empire?”

As the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water prepares to launch its own advisory council, are youth advisory groups worth engaging in with at all?

In 2023, the Office for Youth created a youth advisory group on Climate Change and COP28, alongside four others on various topics. A group of nine young people from around Australia was formed, but disbanded abruptly when the office announced its 2024 youth advisory groups, leaving climate change off the board entirely. Now, the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) has opened applications for its own youth advisory council, another mechanism theoretically designed to ensure that the voices of young people are reflected in government policy.

But why would any young person who is serious about achieving meaningful action sign up? Youth advisory groups are exactly what the name suggests — advisory.

Young people have been advocating for mechanisms that more efficiently incorporate their rights and needs into climate decision making, arguing for substantive protection of these rights. Mechanisms like the Duty of Care bill, which would compel governments to consider the health and wellbeing of current and future generations in the face of climate change, or more broadly, calls to lower the voting age to 16 indirectly force a longer-term perspective.

But neither of these proposals have been embraced. Instead, both proposals have been deflected with the promise of hearing the voices of young people through existing youth advisory groups.

Rather than implementing a mechanism by which they would have to consider the needs and interests of young people, it seems the government prefers to give themselves a choice. They can take this advice, or they can do the polar opposite.

On launching youth advisory groups in 2023, Minister for Youth Anne Aly stated that the government was “committed to embedding engagement structures for young people to ensure they are afforded the opportunity to be heard, respected and can make meaningful contributions to the work of government”.

A member of the Office for Youth’s now-disbanded climate change advisory group stated that in their experience of the group, “tokenism won out once again.”

Rather than the group providing “genuine opportunities to contribute and lead on the agenda important to [them]”, this member said they felt like “another cog in the machine”, with their mandate being to “help the government meet their targets”.

As the DCCEEW prepares to launch its own advisory council, it’s worth asking: are youth advisory groups are worth engaging in? Or are they all work, no reward?

Despite the evident shortcomings of these groups, they do have value when structured effectively.

Youth advisory groups need defined mandates and authority — something that grants them real influence. They need the built-in ability to review policy decisions and implementation, and for their input to become a substantive component of policy development.

The advice from youth advisory groups must lead to something, not dissipate into the ether. And for the effects of youth advisory groups to be felt, and therefore evaluated, these groups need a long-term mandate. Constraining the work of young people in bringing a longer-term perspective to decision making to a short time frame is flawed. Treating them as ongoing consultatants would demonstrate respect for the contributions of young people and foster genuine engagement.

The DCCEEW’s youth advisory council won’t have a long-term mandate, running only until December 2025 according to its website. It also won’t be involved in policy making, sitting under the public service rather than being an arm of government — as the now disbanded climate youth advisory group did. The council’s mandate, as per the website, will be to “provide the minister for climate change and energy practical and innovative advice on issues to support Australia’s commitment to reach net-zero by 2050 and to advance the energy transition”.

Whether this genuinely succeeds in increasing government accountability to current and future generations, or becomes yet another tokenistic, disingenuous mechanism by which to ostensibly integrate young people into climate policy, remains to be seen. If only we had the time to wait.